Authors: David Krch, Vlaďka Laštůvková

At the end of this November, the Supreme Administrative Court rendered a judgment[1] in a dispute concerning the setting of a distribution model in the pharmaceutical industry in relation to VAT, annulling the Municipal Court in Prague’s decision under which a Czech pharmaceutical company was assessed an additional VAT on the consideration for marketing services (related to distribution) provided abroad. The Supreme Administrative Court held that in the present case the distribution of medicinal products and the provision of marketing services constituted two different supplies, since the recipient of the marketing services was not (unlike the distribution) the Czech pharmaceutical company’s customers, but a foreign company. The consideration for marketing services should not therefore have been included in the VAT base. The decisive factor in the dispute was the knowledge of the specifics of the pharmaceutical market.

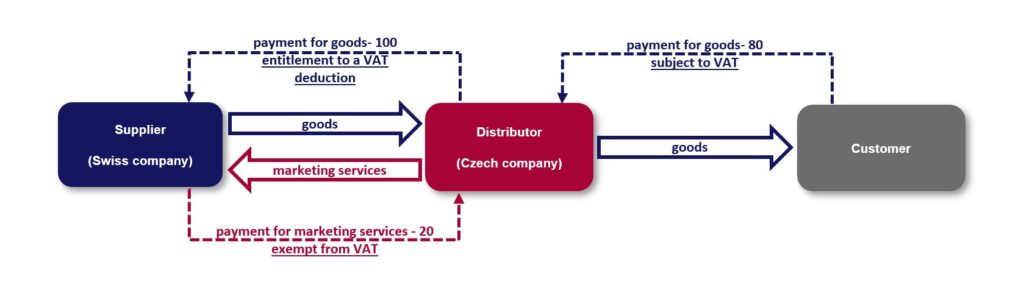

A Czech pharmaceutical company, as a distributor[2] of medicinal products (the “Distributor”), purchased medicinal products from a Swiss wholesaler (the “Supplier”) within the group and subsequently distributed (sold) them further to other persons on the Czech market at a regulated price (lower than the purchase price). At the same time, the Distributor provided marketing services to the Supplier in relation to these medicinal products in return for consideration, which ensured the Distributor’s profitability despite the loss-making sales in terms of transfer prices.

In terms of VAT, within the set model, in the Czech Republic, the Distributor paid VAT on the price at which it distributed (sold) the medicinal products. The Distributor reported the marketing services as the provision of a service with the place of supply outside the Czech Republic and, therefore, the income from such services was exempt from VAT in the Czech Republic (with a right to deduction). As a result, the Distributor was entitled to deduct input VAT at a higher rate than its output tax liability.

When assessing the model in question, the tax administrator concluded that the marketing services as an ancillary supply had been an integral part of the distribution as the main supply, and therefore assessed the Distributor a difference equal to the amount of VAT (excluding the relevant penalties) that would have been paid if the supply from the marketing services related to the distribution of medicinal products had been subject to Czech VAT. In its decision,[3] the Municipal Court in Prague agreed with that conclusion, inter alia, in view of the tax authorities’ assertion that the recipients of the marketing services were in fact the Distributor’s final (unspecified) customers.

More information on the Municipal Court in Prague’s decision can be found in our previous Tax Flash here.

The Distributor disagreed with the Municipal Court in Prague’s decision and filed a cassation complaint against it. The dispute was thus referred to the Supreme Administrative Court (the “SAC”), which finally[4] ruled on 23 November 2021 that the distribution of medicinal products and the provision of marketing services constituted different supplies in the present case. According to the SAC, only the income from the sale of medicinal products should have been included in the VAT base, and not also the income from marketing services.

Judgment of the Supreme Administrative Court

The SAC identified the fundamental question in the entire dispute as the assessment as to “whether or not the distribution of medicinal products and the marketing services provided by the complainant [the Distributor] constitute a single supply for VAT purposes”[5] (a question of law). In order to answer that question, it was necessary to establish “which person or persons were the recipients of the marketing services”[6](a question of fact).

As for the question of fact, the SAC concluded that the recipient of the marketing services in the present case had been the Supplier, not the Distributor’s customers. In justifying that conclusion, the SAC relied, inter alia, on the difference between the provision of marketing information to customers and the nature of marketing services and the specificities of the pharmaceutical market, in particular the different position of individual pharmaceutical companies within the group (e.g., manufacturer vs. distributor[7]), the position of different entities on the pharmaceutical market (i.e. patients, doctors, wholesalers, etc.) and the possibility of providing marketing information concerning medicinal products directly to patients.

When considering the main question in the dispute, the SAC subsequently concluded that the distribution of medicinal products and the provision of marketing services in the present case had constituted different supplies, not a single supply. In addition to the identification of the recipient of the marketing services, the SAC considered, inter alia, the following facts: how the consideration appears from the perspective of the ‘average customer’, whether the prohibition on exceeding the total value of the consideration paid by the final customer is complied with, and the specificities of the pharmaceutical market.

In its judgment, the SAC first of all answered the question whether in the present case the Distributor’s customer could actually be considered the recipient of the marketing services (could not) and made it clear that factual knowledge of the (not only pharmaceutical) environment was crucial for decision-making in similar disputes.

At the same time, the SAC has to some extent alleviated concerns that, following this case, there would be a need to review business models based on similar principles across the pharmaceutical market in view of the increased risk of across-the-board additional VAT assessment on companies applying this model. Nevertheless, it should be stressed out that each business model must be treated individually, and the risks (not only from a VAT perspective) must be assessed in relation to the circumstances of the specific case.

Last but not least, the case under review has shown, in particular taking into account the previous decisions in the case, that in the context of tax audits it is always necessary to proceed with caution and to assess any statement towards the tax administrator comprehensively, since what seems appropriate in one proceeding may cause serious complications in another proceeding.

The authors also add that the SAC’s judgment is also significant for distributors in the pharmaceutical market for the purposes of transfer pricing rules. The fact that distributors across the entire pharmaceutical market in the Czech Republic have been making losses on the distribution of medicinal products for a long time is primarily determined by the system of price regulation of medicinal products applied by the Czech Republic, which in many cases does not allow distributors to generate a reasonable profit.

The result is a situation where foreign suppliers of medicinal products artificially generate and report in their home country a part of the profit from the distribution of medicinal products that should be reported by domestic distributors in the Czech Republic. Ultimately, they have no choice but to seek additional sources of operational financing, such as providing the marketing services back to the group, which were the subject of this dispute.

If this system, which the Czech Republic has enforced from distributors through its price regulation system, were to be further penalised at the distributor level by additional VAT assessments, this would, according to the authors, be a completely absurd situation where the Czech Republic, through its own price regulation policy, is forcing distributors into alternative methods of financing for which it is subsequently penalising them. The authors therefore highly appreciate the quality of the judgment of the SAC that assessed the case very precisely in light of all the specifics of the distribution of medicinal products in the Czech Republic.

[1] Judgment of the Supreme Administrative Court of 23 November 2021, Case No. 3 Afs 54/2020 (the “Judgment”).

[2] In its reasoning, the Municipal Court states, inter alia, that in the package leaflets primarily the Distributor is referred to as the marketing authorisation holder. It is not clear to what extent the Municipal Court distinguishes between the marketing authorisation holder itself and its agent in the territory in question.

[3] Judgment of the Municipal Court in Prague of 5 December 2019, Case No. 6 Af 90/2016.

[4] The case was returned to the Appellate Financial Directorate, which is, however, bound in further proceedings by the legal opinion of the SAC expressed in the reasoning of the Judgment.

[5] Para 33 of the Judgment.

[6] Para 40 of the Judgment.

[7] Similarly, in our opinion, it is also necessary to take into account (although the SAC does not explicitly mention this example) the different position of the marketing authorisation holder and its agent on local markets.